“Didn’t you say you had it under control?” Discover why smart security teams choose GravityZone — before the chaos hits. Learn More >>

Data sovereignty is the principle that digital information remains under the legal authority of its place or community of origin, extending territorial sovereignty into the online world. Enforcing it depends greatly on cybersecurity, as although laws can say where data must stay and who can touch it, it is only technical systems that can prove those limits hold. Without security controls, jurisdictional promises are hard to verify in practice.

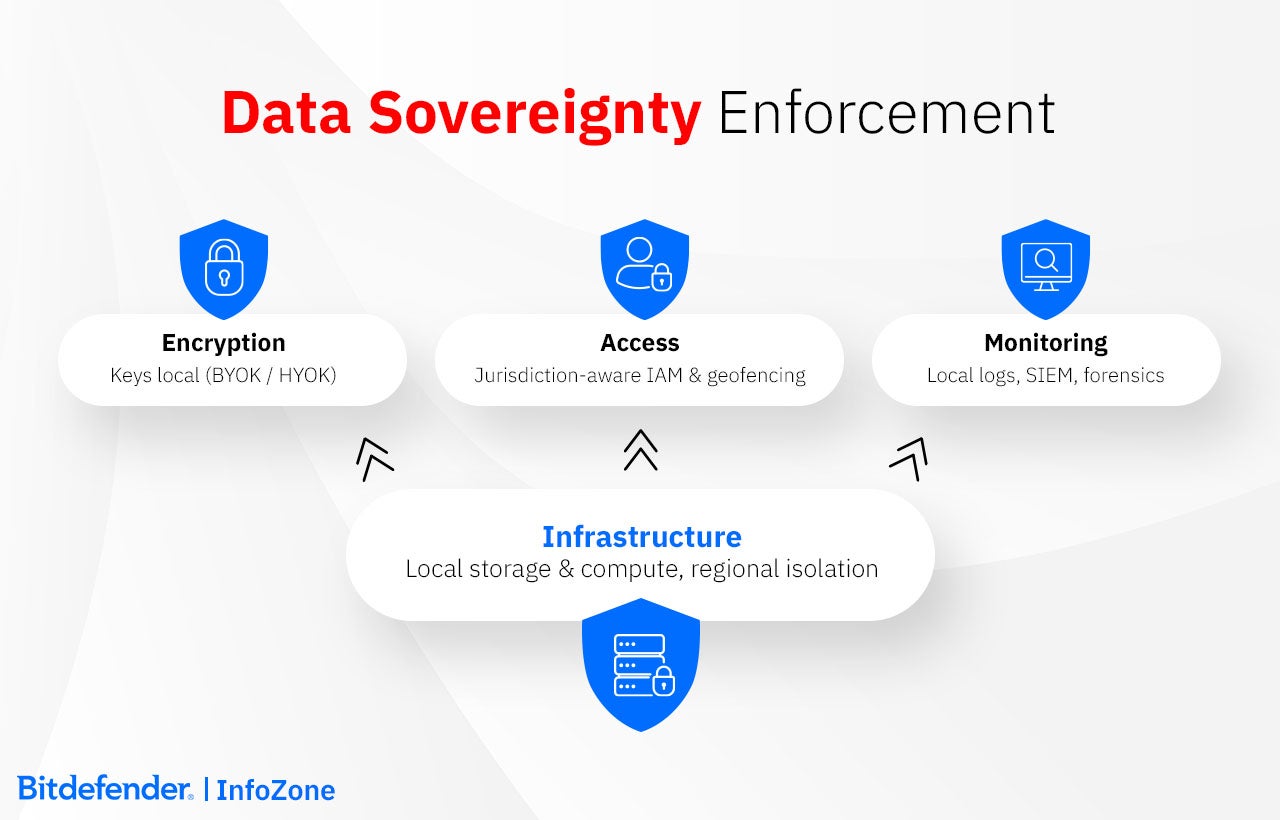

Encryption keeps data safe wherever it travels, but sovereignty adds a second rule: the keys must stay under local control. Access management ties identity to geography, ensuring that someone logging in from abroad can’t reach what local law protects. Segmented networks and localized logs give regulators the evidence they now expect: who accessed what, from where, and under whose authority.

Modern laws treat these mechanisms as obligations, not options. Under the EU’s GDPR and NIS2, under China’s PIPL, or Europe’s DORA for financial institutions, security measures form part of the legal fabric. A company that fails to protect data according to those standards isn’t just insecure, it’s also out of compliance.

Laws can claim jurisdiction over data, and that is an extensive topic in itself (see this InfoZone article). Yet only cybersecurity makes that jurisdiction verifiable. Together, these two aspects form the structure of digital trust, in which one sets the rules, while the other proves they work.

Data sovereignty can hold only as long as there are efficient systems that enforce it. It begins with legal perimeters, but it must continue with transforming them into technical settings. These are anchored in concrete requirements connected to where data lives, how it is protected, who can reach it, how actions are traced, etc. In practice, compliance becomes the engineering problem of building an infrastructure that respects jurisdictional lines by design.

Infrastructure. Location is very important for control, and that is why everything starts with knowing where data sits. The consequence is that the infrastructure must make sure storage and processing stay within approved regions. Also, replication and backups should be confined to the same boundary.

Encryption. The next layer decides who can unlock the information. In order to remove the pathways for external access, no one outside the jurisdiction should be able to unlock encrypted data. That is why encryption keys should be kept locally. This also means that when data must travel, it remains unreadable outside the borders.

Access. Geography also applies to people. Identity and Access Management systems enforce where users log in from and what they can reach. Sessions initiated from unapproved territories are rejected automatically. It is how a global workforce stays within local law.

Monitoring. The last layer proves that the others work. Security logs and forensic records must stay local so that evidence never crosses a border. Sometimes, analysis across regions is necessary. In these cases, it is best to use derived indicators (summaries) instead of raw data.

Sovereignty starts in how infrastructure is built and operated. Some organizations keep all workloads on-premises to maintain full jurisdictional control. Others use hybrid models, hosting sensitive data locally while scaling less regulated processes in the public cloud. Sovereign clouds extend that idea further by ensuring that both the hardware and the operations stay under national or regional authority.

At the technical level, control planes and data paths must remain within the same jurisdiction. The control plane manages provisioning, monitoring, and configuration; if it sits in another country, even local data becomes foreign-controlled. Data paths (storage, replication, and backup) need the same treatment so that no copy or telemetry stream leaves the defined boundary.

Operations decide whether those boundaries hold. Remote administration, patching, and monitoring must be restricted to verified domestic personnel or trusted partners bound by local law. Logs, telemetry, and backups should be routed and stored locally, with failover systems designed to recover inside the same legal zone.

Providers secure the platform, but customers define its perimeter: where encryption keys live, who can access systems, and how external support connects. When infrastructure, operations, and contractual controls align, sovereignty becomes measurable instead of declarative.

The moment data crosses a border, someone has to prove that it didn’t. That single contradiction runs through every technical layer of sovereignty, from encryption keys to access control. Compliance needs that kind of precision. And precision, in practice, is layered.

There are different models used to keep decryption authority inside the right borders. Bring Your Own Key (BYOK), Hold Your Own Key (HYOK), and client-side encryption are some of them. However, it is in fact more difficult to control the keys than to actually encrypt the data. Keys must live, rotate, and expire inside the same jurisdiction, verified through in-region audits. Disaster recovery adds another layer to consider, as backups, failovers, and key replicas must all remain local. The cryptography is mature enough to protect data, but what breaks down first is its implementation.

Access rules that depend on geography look simple on paper but rarely are. People travel, contractors rotate, and global support models blur the clean lines of sovereignty. To stay compliant, some organizations enforce read-only or time-limited sessions outside approved regions; others go further, keeping entire data environments isolated behind regional walls.

Visibility fragments when monitoring must stay within national borders. Each jurisdiction often runs its own SIEM (Security Information and Event Management) and forensic environment, preventing raw log exports or shared dashboards. Coordination depends on derived indicators (malware hashes, attack patterns, anonymized alerts) rather than full telemetry. It works, but more slowly. And lastly, breach-notification rules differ by country. This has resulted in the need to enforce parallel response plans that operate on different clocks.

Compliance today is less about producing declarations and more about showing evidence. As a result, there is an increasing demand for audit-ready systems. These should be able to show where data resides and which personnel accessed it or hold the keys.

Security models based on zero trust strengthen this approach by limiting access to verified users and keeping detailed records of each action.

Another important thing to remember is keeping everything inside the same jurisdiction. Each proof point (location, key custody, personnel clearance, etc.) has to stay within its own jurisdiction. The audit trail itself becomes sovereign.

Doing all this comes at a cost. Running parallel infrastructure, duplicate monitoring, and localized teams introduces real overhead, often called the “sovereignty tax”. It is the premium paid for verifiable control: higher complexity in exchange for lawful certainty and digital trust.

Sovereignty is basically an architectural constraint, and the goal is to enforce jurisdiction in code and infrastructure without collapsing performance or blowing up cost. That means picking patterns that contain data by design, then wiring controls that prove it.

Localized isolation is the purest form of control in which all data, compute, and management planes stay within the same boundary. It is easy to explain to regulators but expensive to run: duplicated systems, local staffing, and disaster recovery that never crosses regions. You gain certainty at the cost of scale.

Federated encryption keeps cryptographic control local even when workloads move. In practice, data can travel for processing, but the keys that unlock it never leave their jurisdiction. It's a practical setup for distributed analytics or model training, though coordination delays and added latency often become part of the cost.

Sovereign cloud models take the middle ground: regional control planes and data paths, standardized controls, and local support teams. The advantage is that they deliver more agility than on-prem environments. However, there is the cost of some capabilities lagging behind global services.

Zero-trust IAM enforces identity by context. Who requests access, from where, on which device, under what conditions are only part of all the things that it takes into consideration. Administrative sessions initiated outside the approved region simply fail.

DLP tools add guardrails by inspecting and blocking data in motion that breaches territorial rules.

CIEM manages the opposite problem: too much privilege. It identifies dormant or over-broad permissions that might bridge jurisdictions.

Finally, region-scoped SIEM and forensics ensure monitoring happens locally. For global correlation which is sometimes needed, derived indicators are shared rather than raw logs (these could expose regulated data).

|

Focus Area |

Objective |

Practical Implementation |

|

High-Watermark Compliance |

Maintain consistent control across regions. |

Use policy-as-code frameworks and CSPM tooling to check whether configurations in every region match the toughest rule that applies. The goal is to make the strictest baseline the default, not the exception. |

|

Vendor & Sub-Processor Governance |

Preserve jurisdiction when control leaves your hands. |

Ask providers to show verifiable proof (such as SecNumCloud, ISO 27001, or SOC 2 Type II certifications) and confirm through APIs or dashboards where replicas and backups actually sit. These checks matter more than a contract clause. |

|

Risk & Resilience Testing |

Expose weaknesses before an auditor does. |

Run resilience drills built around sovereignty risks: what happens if a region goes offline or an offshore admin connects by mistake? Simulate it. Logging, failover, and incident response must all work inside the right jurisdiction. |

|

Privacy-Enhancing Technologies (PETs) |

Support analytics while keeping raw data in place. |

Apply techniques such as federated learning, secure multi-party computation, or trusted execution environments (TEEs) so data stays local while insights travel. Match the method to the workload, as fully local, hybrid, or sovereign-cloud setups each behave differently. |

|

Key Management & Cryptography |

Keep cryptographic control inside the legal boundary. |

Implement BYOK, HYOK, or client-side encryption with local HSMs (Hardware Security Modules) or region-restricted KMS (Key Management Service). Enforce in-region key generation, storage, and rotation. Document key custody and separation of duties between provider and tenant. |

|

Jurisdiction-Aware IAM |

Enforce access based on geography and legal scope. |

Apply geo-bound access policies and network segmentation that restrict administrative actions by region. Integrate continuous verification using Zero Trust identity models to control global workforce edge cases. |

|

Localized Logging & Compliance |

Prove sovereignty through evidence, not declarations. |

Keep logs, telemetry, and forensics local. When global correlation is required, use derived indicators, not raw data. Maintain audit records for data location, key custody, and personnel clearance. |

|

Hardening & Monitoring (PHASR) |

Shrink the attack surface of sovereign workloads. |

Use Proactive Hardening and Attack Surface Reduction (PHASR) measures to disable unnecessary admin tools, keep a close eye on privileged sessions, and tune controls dynamically based on behavior instead of static policies. |

A single incident can cross borders faster than teams can coordinate. When that happens, the challenge is not only stopping the attack but understanding which laws now apply to the data in question. A sovereignty-aware response plan acknowledges that containment and compliance have to move together.

Preparation

Getting ready often means doing the quiet work upfront: matching laws to the data you hold and marking which ones start the clock, like the GDPR’s 72-hour rule.

When a breach hits, teams that already know whom to call (local counsel, forensics, PR contact, etc.) lose less time finding help.

Even small things count; a ready-to-translate notice can spare hours when several authorities demand answers at once.

Detection and Containment

Once an alert surfaces, the question becomes: where is the data, and whose citizens are affected? Containment depends on staying inside those legal boundaries.

Using region-scoped monitoring or XDR tools helps investigators limit data movement and coordinate analysis without exporting logs or evidence abroad.

Post-Incident

After the breach, sovereignty turns into a matter of proof. Evidence has to meet the legal standards of each jurisdiction, and follow-ups with authorities must confirm that containment and recovery stayed within local limits. Teams that combine technical lessons with a legal debrief often emerge better prepared for the next cross-border event.

Data sovereignty rarely fails inside the organization, it usually fails through someone else’s hands. Vendors, cloud partners, and SaaS providers all extend the same legal perimeter, whether or not they realize it. Once data leaves internal control, accountability doesn’t go with it, it stays with the original data owner.

Third-Party Exposure

Sovereignty weak points often hide in vendor operations. A provider may promise local hosting yet run backups abroad or allow helpdesk access from another region. That remote login can be enough to bring the data under a different country’s law, such as the U.S. CLOUD Act. Shadow IT makes it worse: unapproved apps or SaaS tools quietly move regulated data into clouds no one monitors.

Supply Chain Threats

Attackers have learned that it’s easier to go through the supply chain than through the front door. Compromising a single vendor can expose many customers at once, as the SolarWinds incident proved clearly. Offshore administrators or subcontractors with unrestricted access create similar blind spots, effectively extending jurisdiction beyond what contracts ever intended.

Managing Jurisdictional Risk

Control starts with knowing where data really lives and who can touch it. Agreements should pin down storage and replication locations and specify which jurisdictions apply. Technical proof carries more weight than any written assurance.

In the European financial sector, the safest rule is simple: nothing leaves the bloc. This bank runs every workload on EU-only infrastructure: primary systems, backups, even staging environments. Encryption keys are locally generated and rotated through Bring-Your-Own-Key vaults under direct control of the compliance team.

Security operations use a regional SIEM that never exports raw logs, only derived alerts. When drills run, the timer starts at “breach detected” and ends before the 72-hour mark, ensuring that compliance timelines are tested under real conditions. Annual audits verify one thing above all: that every byte of client data can be traced to where it physically lives. The result isn’t glamorous, but it is defensible, and that’s what regulators care about most.

For a U.S.-headquartered financial company processing European customer data, sovereignty risks run both ways. The CLOUD Act gives U.S. agencies the power to request data from American providers, no matter where that data sits, including the EU. The GDPR pulls the other way, forbidding transfers to countries without matching safeguards.

To avoid falling between the two, the company keeps its European operations inside local cloud regions and holds its own encryption keys within the EU. Access is managed through jurisdiction-aware IAM that limits who can see raw personal data and from where. Security logs remain local, with only aggregated indicators shared globally for threat correlation.

These measures don’t make the legal tension disappear, but they give the company proof that EU data stays under equivalent protection, even under U.S. ownership, a balance that regulators increasingly accept as the practical standard.

For a multinational developer serving the Chinese market, the network architecture draws a hard border. Servers, keys, telemetry, everything sits inside domestic facilities. Encryption follows a Hold-Your-Own-Key pattern: the company keeps its key material separate from the host environment, so even the infrastructure provider can’t decrypt data without local approval.

Security monitoring and incident response teams work entirely in-country, with remote access from abroad physically blocked at the gateway.

Each year, the company submits to a state security review, demonstrating that its data flows never step outside national jurisdiction. Although maintaining parallel global and domestic systems is expensive, it is the only way to make sure the business is running within the letter and spirit of local law.

Not every project can live inside one border. In research and manufacturing networks that span continents, participants use data spaces built on decentralized trust. Each organization keeps its data where it originated; computation moves instead of content. Policy-controlled connectors decide who can query which dataset, and for what purpose, enforcing usage rights in real time. Access happens through connectors that check policy in real time: who's allowed to query what, and why. The data itself stays put; what moves are anonymized results or trained models. Local auditors handle their own environments, keeping compliance regional even inside global projects. It's not perfect, but it works better than building walls.

Current popular AI models demand scale and diversity in order to evolve. On the other hand, data laws put borders and divide diversity. In practice, centralized training gives accuracy but violates localization rules. Not all training needs to happen in one place. Some teams now split the process entirely: training locally, swapping compressed gradients over encrypted channels, then retraining to smooth out bias that creeps in when each region sees only its own data.

Another approach countries use is setting up closed research networks that behave like miniature internets. This is a compromise that allows models to learn inside borders while following global trends.

Most experts still agree that quantum computing won’t break encryption tomorrow. That doesn’t mean that the planning for a quantum computing future hasn’t already begun.

Data stolen today may be decrypted a decade from now. The defense is migration, hybrid cryptography that combines classical and quantum-safe algorithms, guided by NIST’s new standards.

What happens when few vendors control too much of the infrastructure? The danger is that jurisdictional control becomes a paper claim. Dependencies hide in update servers, support channels, and subcontractors that no one can quite map.

Mitigation means variety: split workloads, rotate suppliers, and audit the hidden layers of the chain.

Europe’s new rules push resilience from paperwork into real testing. Red-team drills, recovery exercises, and incident rehearsals are no longer optional, but expected. Systems need to prove they can stand on their own when borders close or providers fail. The same pressure is spreading elsewhere. Many organizations now rely on global standards such as SOC 2 and ISO 27001 to show that security controls actually work. These frameworks weren’t written for sovereignty, yet their focus on evidence and repeatable testing fits the direction set by DORA and NIS2. Together, they mark a shift toward security that can be measured instead of merely declared.

Bitdefender GravityZone transforms data sovereignty from policy into technical proof. Built on EU-hosted sovereign cloud infrastructure, the platform integrates the controls needed to secure each enforcement layer (infrastructure, encryption, access, and monitoring) that define a verifiable sovereign architecture.

At the infrastructure layer, GravityZone on Sovereign Cloud Infrastructures (secunet / SysEleven and OVHcloud) keeps storage, telemetry, and management inside approved regions. It's built for localized control and resilience, meeting the practical demands of DORA and NIS2. The setup makes sure data stays under EU jurisdiction, in processing, analysis, and even routine support.

To meet residency and protection requirements, Bitdefender uses layered safeguards for both stored data and system integrity. Full Disk Encryption (FDE) protects endpoint information, with centralized key management and compliance reporting built in. Integrity Monitoring looks past files and into what often causes trouble, changes in registries, applications, or user accounts. It tracks them continuously and flags anything that shouldn't happen.

Access control is where most sovereignty claims are tested in practice. CSPM+ (Cloud Security Posture Management) keeps an eye on cloud configurations, checking them against internal and external compliance rules. Its built-in CIEM (Cloud Infrastructure Entitlement Management) adds a finer layer, trimming permissions so accounts don’t collect excess access over time.

Identity Threat Detection and Response (ITDR) focuses on credential misuse, spotting patterns that suggest lateral movement or privilege escalation. Proactive Hardening and Attack Surface Reduction (PHASR) then closes off what’s left, disabling unused tools and tightening permissions automatically.

When something slips through, containment has to happen fast and locally. Bitdefender XDR and EDR bring together signals from endpoints, networks, identities, and cloud workloads, turning them into a single investigation path. Analysts can trace the full sequence through Root Cause Analysis and see context instantly via the Incident Investigation and Forensics capabilities.

For organizations that need 24/7 eyes on their infrastructure, Managed Detection and Response (MDR) adds continuous human monitoring and live threat containment from Bitdefender’s global Security Operations Centers, including a major SOC based in Romania within the European Union.

Offensive Security Services, including Penetration Testing and Red Teaming, validate that sovereign architectures hold up under real-world attack conditions and satisfy audit expectations for resilience testing under DORA and NIS2.

When people talk about sovereign data, they mean information that a country, community, or other authority claims as being under its own legal protection. In other words, the data is treated as part of that jurisdiction’s territory, even if it’s sitting on a foreign cloud server or processed by an overseas company.

Most of the time, this covers a few familiar types: personal data about citizens or residents; sensitive business or medical information; and what governments call critical data, things like defense files, infrastructure records, or energy system data. Some nations also include intellectual property or research results if they’re tied to national security or public interest.

The idea isn’t limited to states, either. Indigenous communities use the term trying to assert control over data about their people, lands, and traditions.

Not by itself. Data sovereignty decides whose laws apply to your information, but it doesn’t stop someone from exploiting a weak password or an unpatched server. What it does do is force organizations to put the right protections in place. Think of it as the rulebook that makes security a legal obligation, not just a best practice.

Under most sovereignty regimes, encryption isn’t optional, and neither is keeping control of your own keys. That means even if data is stolen, it’s useless without local authorization. Access must also follow “jurisdiction-aware” rules: only cleared people in the right country can touch certain systems, reducing how far an attacker can move if they get in. Local monitoring and audit trails make detection faster, another sovereignty requirement that doubles as good security hygiene.

Where sovereignty really changes the equation is in accountability. A breach in a sovereign environment isn’t just a technical failure; it’s a regulatory one. The penalties for losing control of protected data are severe

Sovereign compute usually refers to the idea that data should be processed in the same jurisdiction where it’s stored and governed. In practice, that means the servers, workloads, and support teams handling sensitive information all operate inside one legal boundary, not scattered across global regions. The intention is to keep computation, not just storage, under local authority.

How this is done varies widely. Some organizations run workloads on private or government-controlled infrastructure; others use “sovereign cloud” environments that isolate management and support within national borders. Hybrid approaches are common too, keeping regulated workloads local while letting routine processing run in commercial clouds.

The real tension is in the trade-off. Cloud platforms are built to move workloads wherever it makes sense, faster, cheaper, more efficient, but sovereignty asks for the opposite. In practice, that means every team ends up drawing its own line between compliance and performance, sometimes moving workloads closer to the law than to the user.