“Didn’t you say you had it under control?” Discover why smart security teams choose GravityZone — before the chaos hits. Learn More >>

Data sovereignty is a term used to describe the principle that information is subject to the laws and authority of the nation (or community) of origin, extending the idea of territorial rule (“state sovereignty”) into the digital sphere. Data itself has become a resource that shapes economies, governance, and daily life. It can shape economies and public services, while also raising dilemmas about individual rights. Such information should remain under legitimate legal protection, the main argument being that this way the world can maintain autonomy and digital trust. Put simply, as a citizen or a company, it is difficult to trust the digital systems most of us operate in without knowing whose laws safeguard your information. That is why, data sovereignty is closely linked to cybersecurity.

Data sovereignty is not the same thing as data residency (this refers to the physical location of data) or data localization (which only describes legal requirements to keep data within a country’s borders). Sovereignty is about jurisdictional control, in other words, the right to govern and protect data. It doesn’t matter where it resides.

As expected, data sovereignty brings a powerful tension between national interest and global interdependence of various states, nations, communities, ethnic groups, etc. Governments obviously try to protect citizens' rights and strategic digital assets. Organizations aim to have high profitability and try to operate across borders without all the friction. These different aims bring numerous challenges when we speak of digital governance.

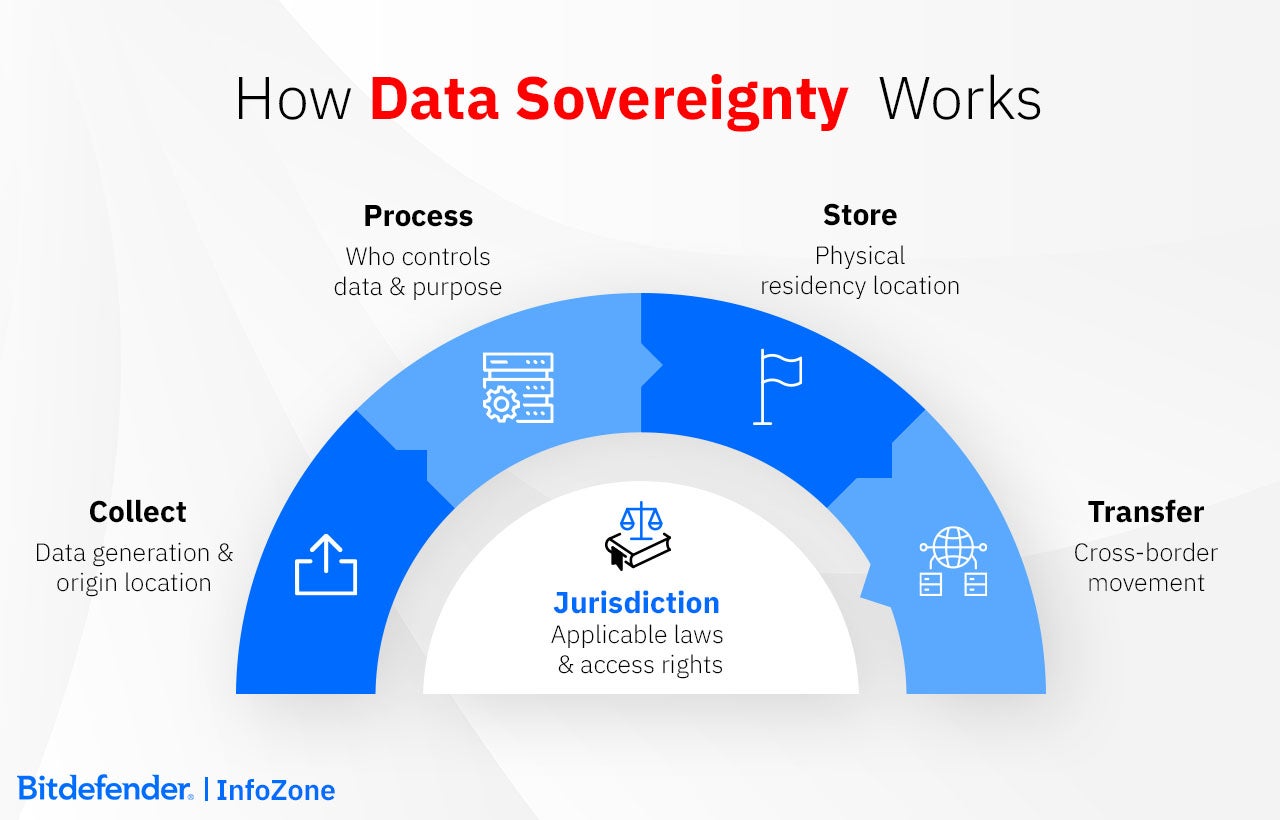

Data sovereignty is not a very straightforward process, and data stored on a country’s servers does not always fall under that country’s laws. Whose laws apply to digital information depends on where the data sits, but also who controls it and which government claims authority over it.

A company may collect data in one place, process it in another, and store it elsewhere entirely. Each jurisdiction can claim legal authority, and their rules can conflict. This is what gave rise to “digital jurisdiction”, the modern idea that a state’s authority over data depends not only on geography, but also on whose data it is and how it affects citizens or institutions. Traditional territorial laws were written for physical boundaries; data moves far faster and rarely stays put.

The confusion this creates isn’t theoretical. In the Microsoft Ireland case (2013), Microsoft refused to hand over some emails that the U.S. authorities demanded, arguing that an American warrant couldn’t reach data stored in Ireland and that this could break European privacy rules. This dragged on until 2018, when the CLOUD Act gave the U.S. explicit power to compel data from American companies regardless of where they reside. However, the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) restricts how European personal data can leave the bloc, which in practice means that an American company that complies with one law can breach another - a legal war that no one fully wins.

Data sovereignty does not necessarily require data localization. It only requires that data remain under the protection of the applicable legal framework, wherever it resides.

When deciding data sovereignty, the most important question to ask is “who makes the rules?” Geography has its importance in the matter, but it is jurisdiction that ultimately decides the issue of sovereignty. A server in Frankfurt can still answer to Washington if the company behind it is American.

The framework has four connected layers that depend on each other.

Geographic Data Control tracks where information sits and where it moves. Location determines which laws apply first. Nothing more, nothing less.

Legal Jurisdictional Authority determines who's actually in charge. Different legal systems often collide on this matter, like when GDPR meets the CLOUD Act. Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) and Transfer Impact Assessments (TIAs) are used as a help in managing these conflicts, as, among other things, they can also clarify which courts and agencies can actually access the data.

Security and Access Governance puts those legal requirements into practice. Authentication happens through local key storage. Geographic restrictions use geo-fenced identities. Privilege levels rely on Zero Trust architectures. These technical controls make sovereignty concrete rather than abstract.

Regulatory Compliance Frameworks like GDPR, NIS2, DORA, and HIPAA verify the system works, often using audits and reporting requirements that force organizations to comply.

Here's a simple way to understand it: where data sits establishes the initial context. Law then takes command. Security controls carry out what the law requires. Compliance checks confirm it's actually happening.

The concept of sovereignty used to belong exclusively to states and governments, but in the digital realm, new concepts push the boundaries:

What started as a government-level legal concept has become a shared responsibility among nations, corporations, and individuals. The responsibility follows the data wherever it goes.

A family of concepts evolved to describe various dimensions of how data is governed. Legal authority, geographic location, and individual rights interact in practice, and understanding them side by side helps clarify how.

Data residency concerns geography. It refers to the physical place where information is stored or processed, usually determined by business strategy or infrastructure efficiency rather than law. A company might host its European customers’ data in a Frankfurt data center to meet performance expectations, yet that decision alone does not change which country’s law governs it. Residency describes where the data sits, not whose rules apply.

Data localization removes that element of choice. It is a legal requirement that certain types of data remain inside national borders. Localization laws are often tied to national security, law enforcement access, or the desire to develop domestic technology industries. Russia, for example, obliges companies to store Russian citizens' data within its territory. In such cases, location becomes a matter of legal command, not convenience.

Data privacy deals with how people’s information is handled: who collects it, how it’s used, and when it can be erased. Laws such as Europe’s GDPR or California’s CCPA give individuals clear rights over that process. These rights follow the person, not the place where the data happens to sit.

Mixing these ideas up can still cause problems. Storing data inside a country doesn’t always mean it falls fully under that country’s law. The same dataset can sit on a local server yet remain under the control of a foreign company that answers to another jurisdiction. In practice, this overlap is what creates the conflicts that data sovereignty tries to solve.

Data sovereignty today shapes how entire economies operate after all the geopolitical events that shattered digital trust in the borderless cloud. Digital systems cross borders faster than laws can follow, and governments, as well as organizations, are realizing that control over information is much more than a matter of compliance.

For businesses, it decides which regulators can act, what penalties apply, and where disputes are settled. Under the EU's General Data Protection Regulation, misalignment can be extremely costly, fines reaching into the hundreds of millions. Global firms consider finance and reputation as core pillars of risk management and today data sovereignty is included among them.

For governments, data sovereignty goes beyond policy papers. It touches national security, data confidentiality, and control over citizen information.

Treating information as a strategic asset keeps sensitive records and critical systems under local authority rather than foreign oversight. The way that access is managed affects how police respond, how hospitals coordinate care, even how energy networks recover during a crisis. And when essential data is hosted abroad, part of a nation’s resilience, and its ability to make independent decisions, moves there too. Keeping essential information within the reach of national law has therefore become a matter of strategic independence and public trust, the foundation on which national resilience now depends.

Reputation and trust follow quickly behind regulation. When an organization cannot guarantee whose laws protect its customers’ data, confidence fades. The loss is not only financial; it erodes credibility in markets where digital trust underpins every transaction. Conversely, clear and lawful data governance has become a competitive asset. Companies that can show where data sits and under which jurisdiction it falls are better placed to win contracts, partnerships, and public confidence.

The same dilemma appears sharply in finance. Open Banking and Europe’s PSD2 directive promote data portability and innovation, yet they also expose financial information to conflicting national rules. Banks must allow customers to share account data with authorized third parties. When that data moves beyond domestic systems, sovereignty questions begin to matter a lot.

The world of data is fragmented, and data sovereignty has the power to create trust, as cross-border data flows are no longer uncertain from a legal perspective, but bound by a mutually agreed framework.

Data rules are surprisingly not all the same and rest on different theories of control.

The United States organizes around lawful access and sectors. The CLOUD Act compels production of data under a US company’s control, even if stored abroad, while FISA 702 underpins foreign-intelligence collection. With no single federal privacy statute, state laws (e.g., California) add a parallel layer of rights and duties.

In the EU, protection is rights-first. The GDPR reaches beyond EU borders and limits transfers unless equivalent safeguards travel with the data. The Schrems II ruling was a 2020 decision by the Court of Justice of the European Union that invalidated the EU–US Privacy Shield over inadequate privacy safeguards. This forced companies to rely on Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) supported by Transfer Impact Assessments (TIAs) that document whether the destination offers comparable legal safeguards.

The EU Data Act widens the frame to industrial and IoT data, extending the Union’s appetite for legal certainty beyond personal data. Several EU member states have expanded the general GDPR framework to reinforce their own digital sovereignty.

France introduced the Cloud de Confiance (“Cloud of Trust”) model to keep sensitive or government data within national control and immune from non-EU jurisdiction. Its SecNumCloud certification, managed by the cybersecurity agency ANSSI, requires approved cloud providers to meet strict security and sovereignty criteria.

Germany follows a similar path through its Bundescloud initiative and local cloud centers for government data. The C5 compliance standard (from BSI) sets security expectations for cloud providers and limits exposure to foreign legal claims such as the U.S. CLOUD Act.

Italy and Spain, while primarily aligned with the GDPR, apply national interpretations and sector-specific rules that reflect their own privacy traditions. Together, these efforts mark Europe’s broader shift toward digital and cloud sovereignty under EU law, a direction now formalized in the European Commission’s Cloud Sovereignty Framework (2025), which promotes measurable standards for legal, operational, and technological independence.

China legislates for state security and control. Its Cybersecurity Law, Data Security Law, and PIPL (Personal Information Protection Law) localize critical or “important” data and require security reviews for transfers. Russia’s 242-FZ takes a hard localization line: Russian citizens’ personal data must be stored on Russian soil, with enforcement to match.

India’s DPDP Act 2023 adopts a hybrid model: cross-border transfers are generally allowed except to countries the government restricts, while sector regulators (e.g., payments) still impose tighter localization in practice.

Beyond borders, sector rules create a second axis of obligation: finance (PCI-DSS, GLBA), healthcare (HIPAA), and defense/critical infrastructure (FedRAMP, CMMC, FISMA). In these sectors, what kind of data you handle can matter just as much as where it travels.

Indigenous data sovereignty relates to community self-determination and is closely linked to the CARE Principles. These are: Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, and Ethics. In practice, First Nations health data can be used by an external project only if there is community approval for its access and use. Also, data management must stay true to the cultural values of the Nations.

A written policy is no longer accepted as proof of compliance, as regulators and customers increasingly demand to see how sovereignty works in real operations regarding the controls, the audits, the evidence trail. That proof usually takes the form of certifications collected over time:

In Europe, assurance has its own vocabulary. Schemes like the EU Cloud Code of Conduct, the EUCS cloud-security framework, and France’s SecNumCloud certification act as the regional shorthand for compliance with EU sovereignty rules.

When requirements overlap, one standard always sets the pace. Most teams choose to align with the strictest regime affecting their data, the one most likely to be tested in an audit. It’s a practical habit that keeps cross-border operations both lawful and trusted.

There is no software that enforces data sovereignty, this is something done through governance. The challenge begins long before any technical control: understanding what data exists, where it moves, and which jurisdictions claim it. Mapping and classifying data by origin and flow is something a business must manage to avoid further problems, and once that picture is clear, compliance comes down to matching each dataset with the laws that govern it, while aligning with the strictest one. Why the strictest? Because it’s easier to scale a single high-watermark standard than to juggle competing local exceptions.

Cross-border movement is where theory meets risk. Every transfer must be justified on paper. This is done through a Transfer Impact Assessment to document exposure, standard contractual clauses to assign accountability, and regular checks to ensure those commitments hold. The same discipline needs to extend down the supply chain. Vendors and subprocessors inherit your obligations, so their compliance should not be simply assumed; it actually has to be tested.

What makes sovereignty sustainable in the long run are policies about retention, minimization, and access. As a general rule of thumb, the less data held and the fewer people who can reach it, the smaller the legal surface. Audits test what policies claim: they look for evidence that data sits where declared and that administrative access stays within jurisdictional boundaries. An organization ready for audit is one that can show evidence without moving data to prove it.

Most failures happen upstream because teams confuse residency with sovereignty, but also because they allow privileged logins from abroad or let shadow IT scatter information until oversight is lost. The gaps created are not technical, but due to failures in governance. Sovereignty compliance is impossible to prove using infrastructure diagrams; it actually needs the paper trail that links data to law. This is the only real method to make the system hold up under any regulator's scrutiny.

|

Best Practice |

How to Apply It |

|

1. Map and Classify Data |

Know what data you keep, where it moves, and which laws cover it. Update the map often and track hidden flows like backups or shadow IT. |

|

2. Apply the Right Laws and Transfer Tools |

Match each dataset with its governing law (GDPR, PIPL, HIPAA). Use SCCs and TIAs for cross-border transfers to document equivalent protection. |

|

3. Follow the Toughest Rule |

When laws overlap, meet the strictest one. It’s easier to manage one high standard than many exceptions. |

|

4. Make Vendors Accountable |

Add sovereignty clauses in contracts and check proof of compliance. Subprocessors share your legal duties, so verify, don’t assume. |

|

5. Avoid Common Compliance Gaps |

Don’t mix up residency with sovereignty. Watch for unapproved tools and access from outside the right jurisdiction. |

Data sovereignty brings control, but that comes at a cost. Running parallel systems for each region, translating the same rules into different legal languages, coordinating across regulators that rarely agree, etc. All these things amount to what’s often informally called the “sovereignty tax.”

And the price isn’t only financial. The loss of simplicity is also considered a burden. Every new jurisdiction adds another layer of contracts, audits, and operational limits. These can seriously slow the flow of information that companies once treated as seamless.

Conflicts between laws deepen that friction. One authority demands transparency; another forbids disclosure. In global operations, a single transaction can sit inside several legal regimes at once, none fully compatible. Interoperability is promised far more often than it exists, and businesses spend more time mapping compliance overlaps than innovating.

Privacy and security are part of it, but so is the economics, in other words, keeping data and the wealth it generates close to home. The policy could have a positive effect on the local economy, but there is also the danger of breaking the digital market into many pieces. Most likely result is that small players will have trouble competing globally.

There has been movement towards finding common ground. Europe’s Gaia-X and the International Data Spaces Association are experimenting with federated systems where control and openness don’t cancel each other out. The ultimate goal is to transform the burden of sovereignty into a desirable outcome that proves data is governed responsibly.

Bitdefender GravityZone brings prevention, compliance, and visibility together in one platform, built and operated entirely in the European Union. For organizations that have to prove not only that their data is protected, but where it’s protected, GravityZone gives them the means to do it. It turns regulatory demands into something measurable, visible in dashboards, logs, and audits.

GravityZone runs on sovereign cloud infrastructures operated with European partners: SysEleven in Germany, and OVHcloud in France. Everything stays under EU jurisdiction, so customer data, configurations, and security telemetry never leave European borders. This removes a major source of uncertainty, and by keeping the full chain of control inside the EU, organizations avoid the usual cross-border tension between the GDPR and laws like the U.S. CLOUD Act.

Compliance Manager offers a clear view of how systems align with frameworks such as GDPR, ISO 27001, NIS2, or SOC 2. It automates the checks and builds the reports that auditors expect to see. It also shows whether controls are actually working day to day.

GravityZone Cloud Security Posture Management (CSPM+) extends this visibility to cloud resources, showing whether configurations and access entitlements still match the organization’s own sovereignty requirements. Risk Management and External Attack Surface Management (EASM) go a step further, mapping exposed assets and third-party dependencies that could put sovereignty commitments at risk.

Sometimes the hardest part of compliance is turning legal language into an actual security plan. Bitdefender Cybersecurity Advisory Services helps bridge that gap, working with legal and compliance teams to build policies, audit frameworks, and procedures that hold up under inspection.

Data sovereignty decides who has authority over information, but it’s cybersecurity that proves that authority can actually be enforced. Once laws define where data lives and who governs it, security teams have to make those rules operational: deciding where keys are held, how access is limited by geography, and how incidents are detected or reported locally.

In short, sovereignty creates the rules; cybersecurity makes them real. The second article in this series looks at what that enforcement looks like in practice, from jurisdiction-aware access controls to localized monitoring and encryption models. Find out more in the article dedicated to the connection between cybersecurity and data sovereignty.

In essence, data sovereignty refers to the legal authority over information. Cyber sovereignty is more concerned about the control over the wider digital environment in which information moves. Explained using a virtual map, data sovereignty would mark where the data sits and establish the laws that apply to it (under whose jurisdiction it falls). Cyber sovereignty is a related principle, and it could be said that it draws the borders around the whole digital landscape, like the cables, servers, platforms, and services that carry that data. The borders on a map are not literal; they are created through the control it exerts over infrastructure, data flows, and platforms, defining where one state’s digital jurisdiction ends and another’s begins.

Over time, good data handling evolved to be described by a handful of rules which are currently the most obvious in how GDPR is structured. These principles used in regulations refer to things such as (1) using people’s information lawfully while being clear about what you’re doing with it. Also, (2) collect only what’s indeed needed, (3) what you collect should be kept accurate, and (4) don’t hold it longer than needed. (5) The data should also be kept secure (technically and in handling) to prevent leaks or misuse. (6) Be able to prove that these ideas aren’t just written in policy but actually practiced.

The regulation also ties everything back to (7) purpose: data gathered for one reason can’t quietly be used for another without consent, and accountability runs through all of it. Those seven principles, of fairness, purpose limitation, minimization, accuracy, storage control, security, and accountability, are less about box-ticking than about showing respect for the data and the people behind it.