“Didn’t you say you had it under control?” Discover why smart security teams choose GravityZone — before the chaos hits. Learn More >>

A backdoor attack is a cyberattack that uses a hidden method of bypassing authentication or security procedures so that the intruder can get into a system without disrupting how the system works, in most cases. The attacker can use this to monitor activity, steal information, and install malicious tools, as persistence is a defining trait of backdoor attacks, alongside concealment.

In many cases, the system operates normally and makes detection difficult, which means that the attacker can return whenever needed. In fact, there were cases of backdoors that lasted for even years before detection.

Backdoor attack is a major cybersecurity threat, but backdoors in themselves are not necessarily created with bad intentions. Sometimes, they are a maintenance hook or support account baked into the software so that a developer can troubleshoot or recover systems. The risk appears when those access points remain undocumented or unprotected. Once discovered, they can be taken over and used as an entryway for attackers. Intent and control make the difference between a legitimate backdoor and a malicious one.

The idea itself isn’t new. In the 1960s, computer scientists referred to similar mechanisms as “trapdoors”, convenient shortcuts for system maintenance. By the 1980s, as computers became connected and widely used, those same shortcuts were being repurposed for exploitation. Ken Thompson’s 1983 lecture “Reflections on Trusting Trust” showed how a backdoor could be hidden inside the software development process itself, setting the stage for the kind of long-term threats that exist today.

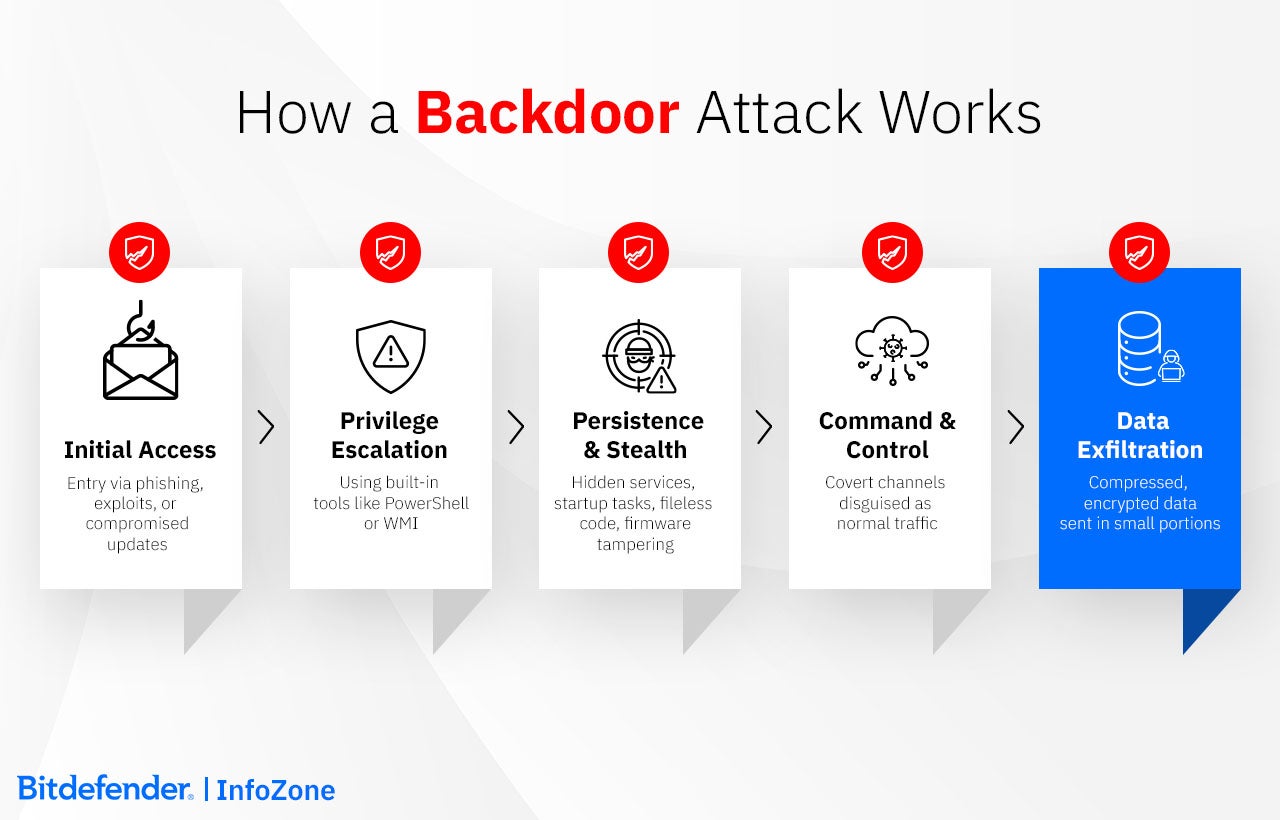

Every backdoor begins with a way in, and what is often used is phishing or other types of social engineering, so that someone inside the system runs a file or shares their credentials. But this is not the only way - attackers could also exploit exposed applications or devices. They use known or unpatched vulnerabilities to install the backdoor directly. Going even more upstream, it is even possible that malicious code is slipped into software updates or development libraries. In simpler terms, a backdoor can even be served to you as part of trusted software.

Once inside, attackers often seek higher privileges so they can move freely. They use built-in administration tools such as PowerShell or WMI to avoid detection — a method known as “living off the land.” Because these utilities already exist within the system, their activity blends in with normal operations.

After an attacker gets in, the next goal is blunt and practical: make that access stick. Backdoors do this by changing things that run automatically on a machine (tweak startup settings, drop a scheduled task, register a hidden service), and in the worst cases, they even alter firmware or boot code so the implant survives reinstalls.

Not all backdoors leave files behind. Some are fileless, living only in memory; others lean on living-off-the-land (PowerShell or system scripts) so their activity looks like routine admin work. You’ll also see code-signing abuse, valid certificates used to make malicious binaries look legitimate, and occasionally rootkit components added to hide processes or blunt logging. The throughline is the same: stay active while leaving as little evidence as possible.

The backdoor maintains communication with the attacker’s command infrastructure through connections made to look ordinary. Using web traffic, DNS requests, or cloud APIs, they blend into daily network activity. To make blocking or tracing them more difficult, attackers sometimes change their servers.

Through these same channels, information is quietly sent out. Data may be compressed, encrypted, and transferred in small portions, or temporarily stored in legitimate cloud services before final exfiltration.

Each phase of this process is designed to stay unnoticed. Detecting such attacks requires visibility into endpoints, network traffic, and cloud activity, all the subtle signals that, when seen together, reveal a backdoor’s presence.

Malware is still a common doorway. Trojans pretend to be useful software and quietly install components that phone home, giving an attacker a covert control channel. Some families (Gh0st RAT and newer strains such as PlayfulGhost) are built to hide in plain sight, piggybacking on normal traffic while giving an operator hands-on control of a machine for everything from file theft to screen capture. Rootkits sit deeper; they don’t just open access, they help hide it, changing what the system reports so defenders never see the real picture.

Rootkits go deeper. They operate at the kernel or driver level, hiding both the backdoor and its activity from system monitoring. Stuxnet showed how deep this can go. It slipped into industrial controllers, made everything look normal on the surface, and changed how the equipment behaved underneath. Modern attackers push that idea further with what’s known as bring your own vulnerable driver (BYOVD), taking a perfectly valid, signed driver and turning its weakness against the system to kill protections before settling in.

Not all backdoors rely on files. Fileless ones live in memory and use trusted system tools (PowerShell, WMI, or scheduled scripts) to execute commands. This approach, often called living off the land, lets attackers operate through legitimate utilities that security products rarely block. They don't drop obvious files, so to spot them, one should rather look for odd behavior than malware signatures

Software can hide backdoors, too. This can be due to a mistake (like leaving a debug feature), but it can also be that a software flaw was discovered and used for access and persistence (see the famous Log4Shell vulnerability).

Web shells are small scripts that let someone send commands through a browser, and they are common on web servers. If they aren't fully deleted, they come back after updates and give the attacker access again.

There are also cryptographic backdoors, where an encryption algorithm is built with a weakness on purpose.

Backdoors introduced through the software supply chain are dangerous because they arrive disguised as trusted updates. When attackers compromise the code or build process of a vendor, their malware is delivered straight through legitimate channels. The SolarWinds SUNBURST campaign and the XZ Utils compromise showed how a single infiltrated dependency can reach thousands of systems. As software development grows more interconnected, one weak link can cascade through every product depending on it.

Backdoors in cloud environments often begin with small mistakes, a permission set too wide or an API key left exposed. From there, attackers can stay inside virtual workloads or containers and blend into the noise. In AWS Lambda, Azure Functions, or Kubernetes, malicious code can pass for routine activity, so it’s rarely noticed right away. Sometimes the problem starts even earlier, with a poisoned container image or a reused credential that quietly turns cloud storage into a route for data theft or remote control.

Backdoors aren’t limited to software. They also appear in routers, firewalls, and device firmware, areas that typical endpoint tools never inspect. In the Juniper ScreenOS case, a hidden flaw allowed attackers to log in with full privileges and read VPN data for several years before discovery. The problem goes beyond networking gear. A lot of consumer devices ship with credentials baked into ROM, which effectively hands attackers an easy entry. Firmware and network kit should be treated like software supply, therefore, one should inventory it, verify it, and assume it needs different processes to fix.

A newer class of attacks targets artificial intelligence itself. By adding hidden “trigger” patterns into training data, an attacker can cause an AI model to behave normally most of the time but produce controlled outputs when the trigger appears. A surprisingly small amount of tampered training data is enough to embed a trigger into a model. We've already seen cases where pre-trained models uploaded to public repositories carried hidden behavior, from quietly running unauthorized code to exposing information during normal use.

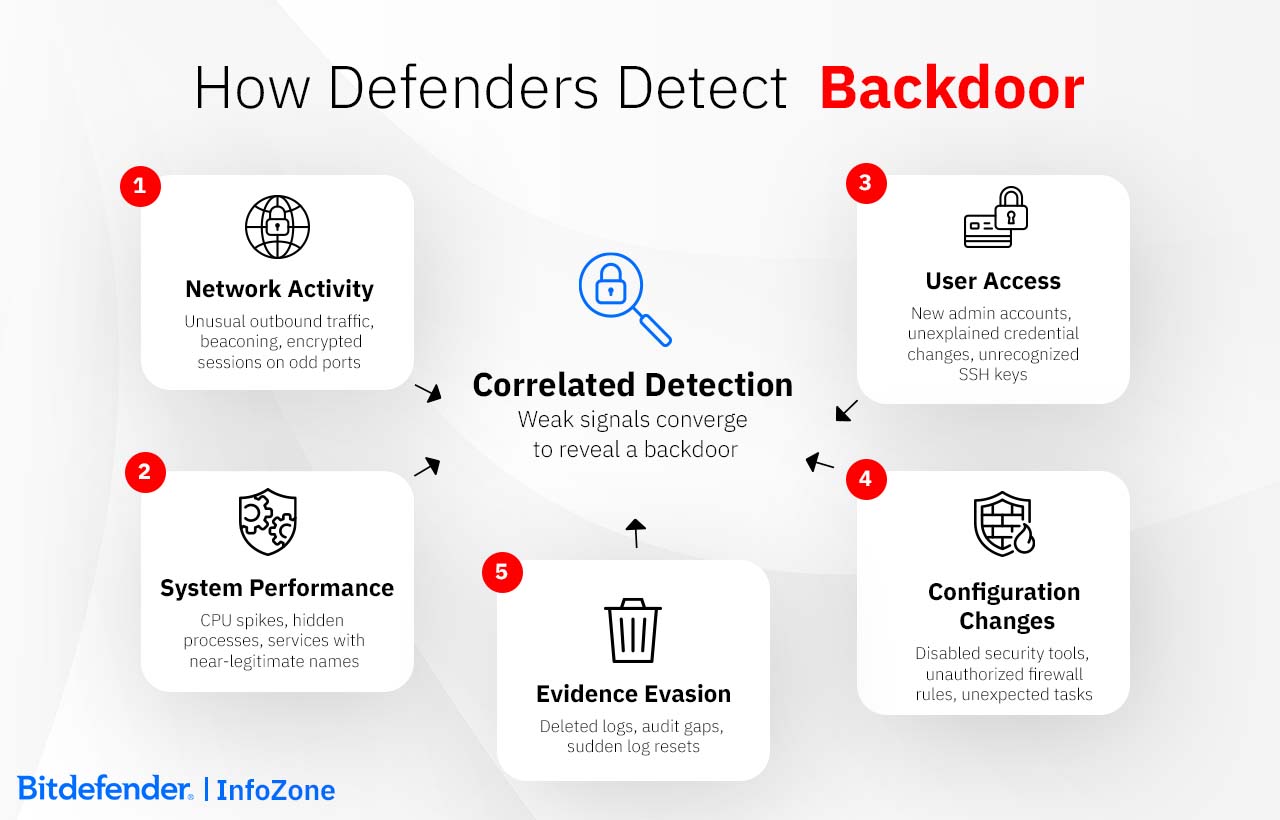

A backdoor tries to pass as ordinary system activity, but sooner or later its presence bends patterns that should remain predictable. The key is to look for elements that begin to behave “almost” normally, particularly within network traffic, system configurations, or user privileges.

Backdoors blend into legitimate operations and leave only a few technical fingerprints, which individually aren’t considered definitive clues. Put together, they don’t look so harmless and should prompt further examination.

|

Category |

Observable Indicators |

|

Network Activity |

Outbound traffic to unknown or foreign IP addresses, especially at unusual hours; recurring low-volume “beacons” to remote servers; encrypted sessions over nonstandard ports. |

|

System Performance |

Unusual behavior such as periodic slowdowns, sudden CPU spikes, or system services running in the background under names that look almos, but not exactly, like legitimate ones. |

|

Configuration Changes |

Security tools being turned off without explanation, startup settings that no one on the team remembers configuring, unexpected scheduled tasks, or firewall rules that quietly open ports you never approved. |

|

User Access |

New admin-level accounts that weren't requested, credential changes with no ticket behind them, or SSH keys appearing in authorized lists despite no tracked deployment. |

|

Evidence Evasion |

Deleted or missing event logs, gaps in audit trails, or sudden log resets following other anomalies. |

As we said previously, one such signal could be a simple false positive, so what matters is how these indicators correlate. Static scanning tools tend to overlook activity that only stands out once you line up different signals, like odd network traffic next to endpoint behavior, or an unexplained privilege change paired with a service modification. Threat hunters rely on that kind of cross-view analysis to surface persistence mechanisms, combining telemetry with file-integrity data and their own judgment.

After establishing persistence, attackers rarely act immediately. They observe, collect, and extract data in small portions to stay below detection thresholds. The same foothold later becomes a launchpad for heavier operations, like ransomware deployment or system manipulation.

The damage isn't limited to systems or stolen files. When personal or regulated data is involved, organizations can face GDPR or HIPAA consequences, along with the reputational fallout that comes with public disclosure. Even backdoors justified as “lawful access” have ended up being exploited by others, a reminder that once a secret entry point exists, someone will eventually find it.

Every cyberthreat has a signature. Ransomware shouts, viruses spread, Trojans deceive. A backdoor does none of these, it stays quiet and waits. Unlike “front-door” breaches that rely on stolen passwords or social engineering, a backdoor skips authentication altogether, embedding hidden access directly into systems.

|

Threat |

What It Does |

How a Backdoor Is Different |

|

Credential Theft |

Steals usernames and passwords to sign in like a real user. |

A backdoor doesn’t need to log in. It creates its own way into the system. |

|

Infostealers |

Take stored passwords, cookies, or browser data, then remove themselves. |

Infostealers grab data once and leave. A backdoor stays active for future use. |

|

Rootkits |

Hide malicious files or code from security tools. |

A rootkit hides the malware. A backdoor is what attackers use to come back and control it. |

|

Encrypts files so that attackers can ask for payment (ransom) to unlock them. |

Backdoors are used to map systems and exfiltrate data before the encryption phase. |

|

|

Trojans |

Pretend to be safe software so users install them. |

The Trojan gets inside. The backdoor is what stays behind once it does. |

|

Spread automatically to other systems, sometimes slowing or crashing them. |

A backdoor doesn’t spread. It stays on one system and keeps a steady connection open. |

|

|

Use a new, unfixed software flaw to break into a system. |

The exploit works once to get in. The backdoor keeps that access after the flaw is patched. |

Backdoors often link separate attacks together and keep intruders in place for the long game. State-sponsored groups use them to run espionage quietly for months or even years. Some hide in firmware or driver code, surviving full system wipes. Others linger in cloud workloads or IoT gear through weak passwords or open APIs. Indirect methods (SEO poisoning, malvertising, and similar tricks) can just as easily drop the first piece of code that sets a backdoor in motion. It's a reminder that persistence isn't the only problem; the real challenge is stopping hidden access from settling in at all.

Preventing a backdoor from taking hold isn’t about a single tool or platform. It’s about staying alert to what changes inside your environment: who connects, what runs, and what shouldn’t be there. Layered visibility across endpoints, networks, and cloud workloads is where real prevention starts.

Run regular security audits and network scans with purpose, not as checkboxes. Old credentials, forgotten admin interfaces, and unpatched apps are what attackers use to slip in quietly.

Pair those reviews with behavioral monitoring. Look for things that don’t fit: traffic going out at odd hours, a service that starts itself after every reboot, permissions that suddenly change.

Centralized Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) or Extended Detection and response (XDR) platforms help connect those dots. Feed them with threat intelligence so they can block known command-and-control servers before contact is made. Add file integrity checks and proper log collection, the simple things that show when someone’s trying to stay hidden.

Keep your systems tight. Keep patches current, don’t skip an update because it looks minor. Firewalls and antivirus tools help, but EDR and XDR are what spot strange process behavior and in-memory threats that old tools miss.

Segment the network. For example, if an IoT camera gets hit, reaching the production servers from it is simply unacceptable. Keep access tight. Give each account only the rights it needs (least privilege rule), and make MFA mandatory for every admin, no exceptions.

Threat-intel feeds, once implemented, help your systems to spot and block new command-and-control domains as soon as they appear.

A lot of backdoors come from the inside, not on purpose, but through sloppy code or missed cleanups. A secure development lifecycle (SDLC) with code reviews, dependency scans, and the removal of test hooks keeps that risk low.

And people still matter most. Train staff to recognize phishing, fake updates, and requests that don’t make sense. Encourage them to report fast; the first person who spots something strange often decides how far an attack goes.

If a backdoor is suspected, time is everything.

Maybe this is not a very exciting work, but doing it right turns a hidden breach into a short event instead of a months-long problem.

The hardest part about tracking backdoors isn’t finding the malware, but rather finding where it was inserted. In recent years, attackers have stopped slipping code into endpoints and started aiming at the systems that ship the code itself.

Is there any lesson that cybersecurity teams can extract from these famous cases? Yes, and they all stem from the same weak spot these had in common: too much trust in code that wasn’t being verified or monitored after deployment.

GravityZone is the core platform behind Bitdefender’s security stack. It brings the main pieces together so defenders aren’t jumping between hardening, detection, response, and visibility tools when dealing with something as evasive as a backdoor.

To reduce the chances of a backdoor being planted in the first place, Risk Management highlights weak configurations and exposed services, and Patch Management handles the missing updates that attackers keep reusing. Email Security catches phishing attempts and malicious attachments, which still remain one of the simplest ways to deliver the initial payload.

Modules like PHASR (Proactive Hardening and Attack Surface Reduction) and Fileless Attack Defense limit the use of PowerShell, WMI, and other built-in utilities that attackers lean on when they don’t want to leave obvious binaries behind. In cloud environments, CSPM+ checks identity settings, permissions, and API exposure, the sort of gaps backdoors rely on heavily.

If something gets through anyway, EDR and XDR collect and correlate activity from endpoints, network traffic, and cloud workloads. That correlation is what usually exposes persistence methods or lateral movement patterns. Network Attack Defense (NAD) helps here by monitoring outbound traffic and blocking suspicious connections or protocol misuse that looks like C2 traffic.

Integrity Monitoring looks at the places attackers usually alter: core files, registry keys, service definitions, configuration values.

When an unknown binary or script appears and static inspection isn't enough, Sandbox Analyzer isolates it and executes it safely so the team can see what it actually does.

Some teams also need help beyond automated tools. Bitdefender MDR handles continuous monitoring and brings human threat hunters into the loop when an intrusion needs quick action. For a more proactive check, the Offensive Security Services group (red teaming and penetration testing) can run the same techniques attackers use to plant a backdoor and show which defenses fail under real pressure.

Backdoors turn up most often in places where long-term access is valuable. The bulk of state-backed activity is covered by organizations such as government agencies, defense contractors, big telecom or energy providers, and because a single foothold gives attackers a lot of visibility, they tend to be priority targets.

Tech vendors are high on the list, too. Compromising a build system or open-source maintainer can quietly reach thousands of customers, which is why supply-chain cases like SolarWinds and XZ Utils were so damaging.

Financial services, crypto firms, and healthcare draw more crime-driven campaigns. Here, a backdoor is simply a stable point to steal data or move money without tripping alarms.

And there’s a long tail: smaller suppliers, hosting providers, and web-facing services get targeted mostly because they’re easier to breach and often connect to bigger environments.

In short, any industry with valuable data or widely trusted software becomes a target, but government, critical infrastructure, tech vendors, finance, and healthcare see it most clearly.

RCE (Remote Code Execution) is usually the point where the attacker gets to run one arbitrary command on the target. That’s enough to pull a small loader, write a file, create a service entry, or register some startup logic. Once that runs, the backdoor is in place and no longer tied to the original vulnerability. Even if the RCE is patched right after, the persistence mechanism stays.

From there, the exploit itself stops mattering. The vendor can fix the bug the same day, but the system remains exposed because the backdoor has already been written somewhere the machine will keep executing, like a startup entry, a scheduled task, a web shell, whatever the attacker chose to leave behind.

Some backdoors also let the attacker run code directly through them, so the RCE part shows up only once. Everything after that (commands, tooling, collection) flows through the backdoor’s own channel.

Yes, and not just through the usual “malicious app” angle. Mobile devices inherit problems from every layer they’re built on: the OS, the firmware, the carrier add-ons, the OEM’s custom Android build, and even the supply chain that loads software before the device ever reaches a store shelf.

For example, some budget Android phones shipped with Triada already embedded in the system image, which meant the backdoor existed before the user powered on the device. Certain modem implementations on older Samsung models exposed file access through diagnostic commands most users never see. There was also the case of ZTE devices where debugging functions were left enabled in production firmware, effectively creating a remote entry point.

Modern attacks haven’t gone away; they just shifted. Zero-click exploits in messaging stacks (like the ones used before Pegasus installs itself) don’t need user interaction at all. Chrome and WebView bugs have also been used to bootstrap code execution on Android with nothing more than a bad webpage. And corporate phones pick up a different category of risk entirely: authentication tokens, VPN profiles, and cloud sync credentials stored locally.